Can you be a citizen of two countries? Absolutely! That’s the message at workshops with dual sponsorship: the Immigrant Law Center of Minnesota and the Mexican Consulate in Minnesota. ILCM’s part in this project is to provide information on becoming a U.S. citizen and to offer screening and assistance to people who want to become U.S. citizens. Blanca Sánchez Rangil, a 2017 Macalester grad working as a legal assistant at ILCM, answered questions about the project:

What is the Dual Citizenship project?

ILCM is doing ten workshops at the Mexican consulate or with the mobile Mexican consulate in Minnesota, Wisconsin, North Dakota, and South Dakota – that’s the first part.

The second part is to help Mexican permanent residents to apply for U.S. citizenship.

What are these workshops?

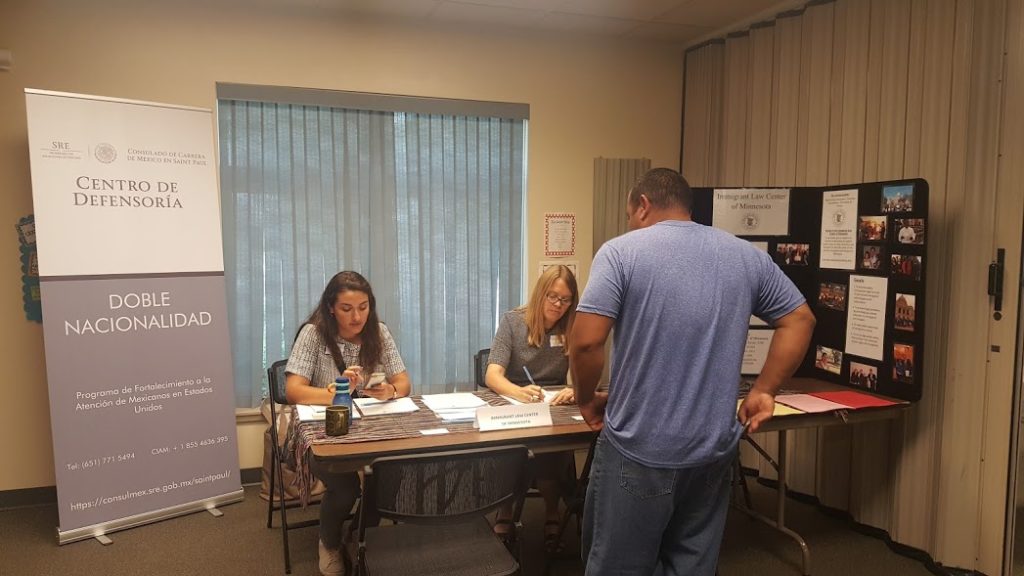

They are basically talks about what citizenship is, the requirements for applying for U.S. citizenship, the advantages, and the process. We just talk briefly about those things. Then the people at the event come talk to us and we do a short screening for eligibility for naturalization. Then I talk to my supervisors back at the office to see if we can help these people.

So it’s a short presentation and the rest of the time talking to the people to see if they qualify.

What is the mobile consulate?

The Mexican consulate in St. Paul tours Minnesota, Wisconsin, North and South Dakota because that’s the area that they serve. They bring equipment and staff to different places for Mexican who live there to renew their passports or get what they call a matricula consular – an identity card.

How can immigrants qualify for U.S. citizenship?

You can apply for citizenship when you are a permanent resident in the United States and have been a permanent resident for 5 years (or 3 years if you are married to a U.S. citizen), and if you don’t have serious past convictions or a problematic immigration history.

What do you tell people are the advantages of citizenship?

They can no longer be deported; they can travel in and out of the U.S. as many times as they want; they can vote in U.S. elections; they can petition for visas for family members – parents, children, siblings.

Why would people not become citizens?

Some people wait if they don’t speak English and they think they can’t learn it. There are a few exceptions when you don’t need to take the test and interview in English but can do it in your native language. If you are 50 years old at least and have been a U.S. legal resident for 15 years, or if you are older than 65, you can get a simplified test.

What do people need to do to become citizens?

They need to complete the application for naturalization – it’s called N-400. There’s a $725 fee. They might be able get a fee waiver if they have a low income.

Then they will receive a notice to get biometrics – fingerprints and photo. In the process of approving the application, they do an FBI background check and also an immigration records check.

After that, they’ll have an interview with an immigration officer. The officer asks them questions about their application.

They also need to take a U.S. civics test. After that, the officer can either recommend for approval or take more time to review the application and think about it.

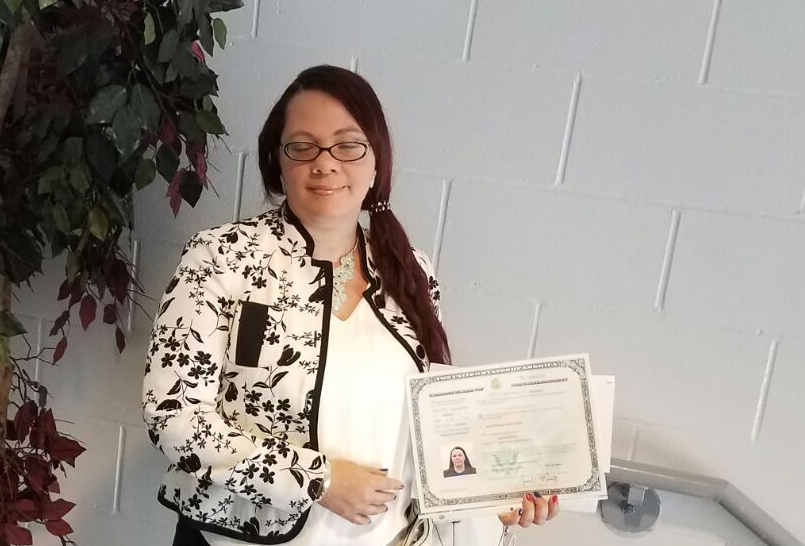

If the application is approved, they get an notice to attend an oath ceremony. There, they are asked a few more questions about their application and they take the oath of allegiance and they become citizens.

Why do you think this program is important?

I think that having free services for people who qualify and knowing how beneficial it is for most of them to become citizens is very important.

Eh Mwee is a bridge builder, though she looks too small to do that work. The bridges she builds reach from employers in Mower and Freeborn counties to Karen and Karenni refugees looking for jobs in their new home.

Eh Mwee is a bridge builder, though she looks too small to do that work. The bridges she builds reach from employers in Mower and Freeborn counties to Karen and Karenni refugees looking for jobs in their new home.

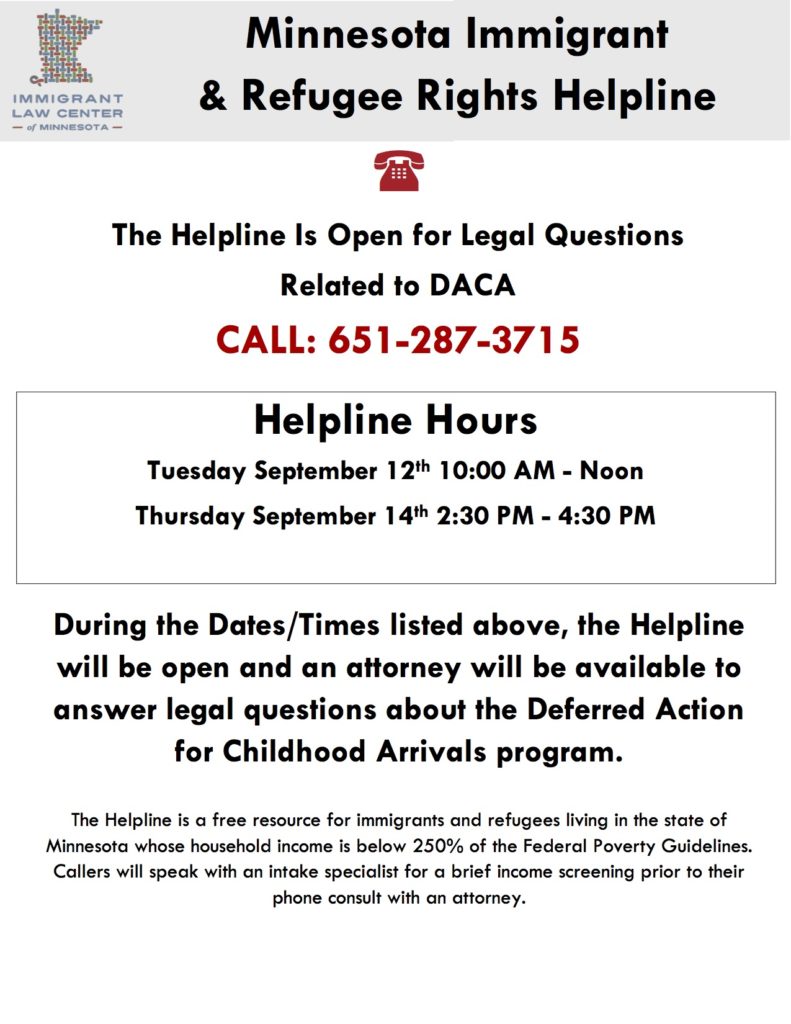

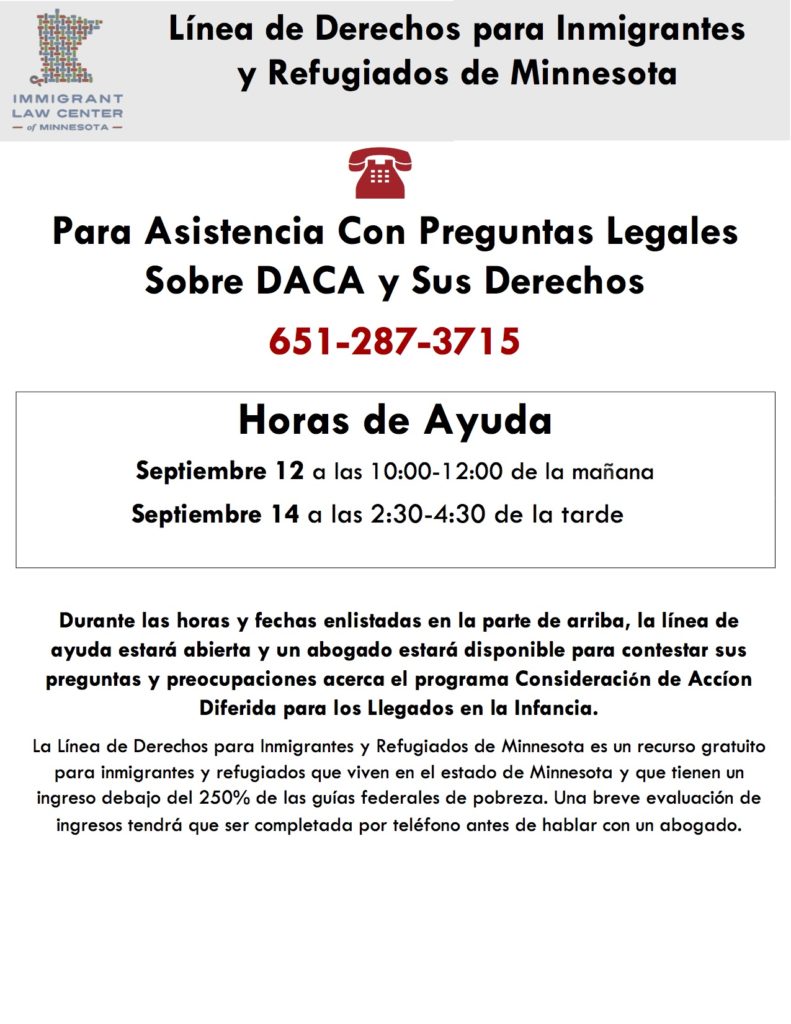

(Español abajo.) The helpline is open again this week! Minnesota immigrants and refugees with household income below 250% of the federal poverty guidelines can call for free legal consultation on DACA. Call 651-287-3715 from 10-noon on Tuesday and from 2:30-4:30 on Thursday. (Income screening will be done over the phone.)

(Español abajo.) The helpline is open again this week! Minnesota immigrants and refugees with household income below 250% of the federal poverty guidelines can call for free legal consultation on DACA. Call 651-287-3715 from 10-noon on Tuesday and from 2:30-4:30 on Thursday. (Income screening will be done over the phone.)