To cut back on immigration, Sessions wants to remove domestic abuse as a legal justification for seeking asylum.

Archives

Trump is mobilizing the National Guard to the US-Mexico border for literally no good reason

The Trump administration says “the threat is real.” But border crossings are at historic lows.

State of immigration: Where new Minnesotans have come from, from statehood to today

In the late 1800s, more than a third of Minnesotans were foreign-born. Today it’s less than one-tenth.

Refugees in Minnesota: Quick Facts

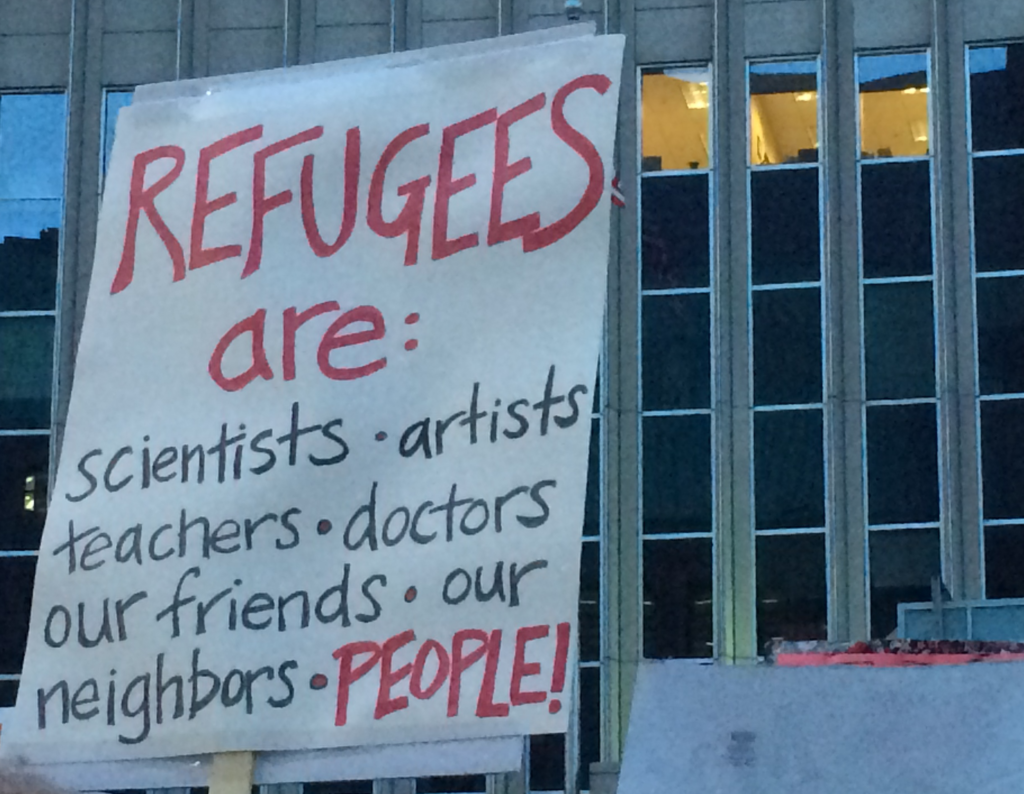

Who are the refugees?

(updated 4/5/2018) (Click here to download PDF version)

- Under U.S. law, refugees are people forced to flee their country of origin due to persecution or a well-founded fear of persecution based on: race, religion, nationality, political opinion or membership in a particular social group.

- Refugees are the most screened migrants to enter the United States. After they are screened by the United Nations, they undergo a U.S. screening process involving eight security agencies and lasting a minimum of 18-24 months.

- Fewer than 1 percent of the world’s refugees resettle to a third country, most remain in refugee camps or return to their home countries. Refugees who resettle in the United States come here to begin their lives anew, in safety and dignity.

- Minnesota has the highest number of refugees per capita of any state, according to the U.S. Census and refugee support agencies. We have a rich history of welcoming refugees because Minnesotans believe in treating all people with respect, dignity and compassion.

Refugee Contributions to Minnesota

- After their first years of adjustment, refugee incomes rise rapidly, and so do their contributions to taxes and the economy. Refugees pay back the cost of the airfare for coming to the U.S.

- Refugees join the workforce, own businesses, pay taxes at the federal, state and local levels, and spend money.

- In 2014, 40 percent of Fortune 500 companies in Minnesota were founded by an immigrant or the child of an immigrant. These firms employed more than 264,000 people world-wide.

- Nation-wide, in 2015, 13 percent of persons who have had refugee status (about 180,000 persons) were entrepreneurs. This high level of entrepreneurship is compared to 11.5 percent of non-refugee immigrants and 9 percent of the U.S.-born population. According to a New American Economy report, in 2015, refugee-owned businesses generated $4.6 billion.

- In Minnesota, refugees contributed $227.2 million in state and local tax revenue in 2015. Immigrants and refugees spent $1.8 billion in Minnesota in 2015.

- As the local workforce ages, immigrants, including refugees, enter the workforce to fill the gaps in labor force growth. According to the New American Economy report, “by 2030, 20.3 percent of the U.S. population will be older than 65, up from just 12.4 percent in 2000.” In 2013, immigrants in Minnesota contributed more than $1.5 billion to Social Security and Medicare.

- Most labor force growth in Minnesota since 2010 can be attributed to immigrants.

- Immigrants, including refugees, are a critical part of the manufacturing, technology, transportation, and health care sectors in Minnesota.

- In Minnesota, immigrants, including refugees, comprise 9 percent of the state’s workforce, 6 percent of the state’s business owners and accounted for 7.5 percent ($22.4 billion) of Minnesota’s GDP in 2012. Immigrants and refugees own 11 percent of the businesses in the Twin Cities metropolitan area.

- The national refugee quota was cut from 110,000 in 2016 to 50,000 in 2017, and to 45,000 in 2018, and the actual number admitted is likely to be even fewer. The shortfall will impact states like Minnesota, which rely on refugee workers to continue growing the economy.

- Refugees contribute to the cultural richness of the state: Since 1979, Minnesota welcomed refugees from more than 100 countries and host communities have benefited in the way of exposure to new languages and cultural traditions.

The H-4 Visa Classification

American Immigration Council Fact Sheet, March 26, 2018

Attracting and Maintaining Global Talent

Temporary workers—such as those in H-1B status—typically can bring their spouses and children with them to the United States in what is called H-4 status. Many of those spouses have careers of their own or otherwise need to work to support their families. Providing work permits to the spouses makes the United States an attractive place to work. Therefore, since 2015, the federal government has granted work permits to certain spouses of H-1B workers.

This fact sheet provides an overview of the H-4 visa category, details the characteristics of H-4 recipients, explains the work eligibility of certain H-4 spouses, and describes the benefits of continuing to allow these H-4 spouses to work.

Rules Governing the H-4 Visa Category

The H-4 is a temporary, nonimmigrant visa category for the spouses and unmarried children under 21 years of age (dependents) of individuals in one of the following nonimmigrant visa categories:

- H-1B (workers in a specialty occupation)

- H-2A (temporary or seasonal agricultural workers)

- H-2B (temporary non-agricultural workers)

- H-3 (nonimmigrant trainees, other than medical or academic)

The H-4 status of an eligible spouse or child is dependent on the primary worker maintaining a valid immigration status. Thus, these individuals are referred to as “H-4 dependents.”

H-4 dependents can attend school. However, they are not eligible for temporary employment related to their field of study—something available to some foreign students, such as those in an F-1 status.

H-4 dependents can apply for an extension to remain in the United States with their spouse or parents, but the length of stay cannot exceed that of the primary worker. Further, H-4 dependents can apply to change to another nonimmigrant status.

Characteristics of H-4 Visa Recipients

The number of H-4 visas allocated to family members of H-category nonimmigrant workers increased from 47,206 in Fiscal Year (FY) 1997 to 136,393 in FY 2017. Overall, the majority of H-4 dependents come from Asia (Table 1).

In FY 2017, most H-4 visas were issued to family members of foreign workers from India (86 percent), China (3 percent), Mexico (2 percent), the Philippines (1 percent), and South Korea (1 percent) (Table 1).

Table 1. Total H-4 Visas Issued Fiscal Years 1997-2017, by Top Countries

|

Fiscal Year |

Total Number of H-4 Visas Issued |

Countries with Highest Number and Percent of H-4 Visas Issued |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

India |

China |

Mexico |

Philippines |

South Korea |

|||||

|

|

|

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

|

1997 |

47,206 |

17,693 |

37 |

2,107 |

4 |

2,060 |

4 |

1,766 |

4 |

859 |

2 |

|

1998 |

54,595 |

24,303 |

45 |

2,562 |

5 |

1,791 |

3 |

1,818 |

3 |

964 |

2 |

|

1999 |

69,194 |

32,711 |

47 |

3,480 |

5 |

1,964 |

3 |

2,217 |

3 |

2,319 |

3 |

|

2000 |

79,518 |

38,705 |

49 |

3,769 |

5 |

1,922 |

2 |

2,387 |

3 |

2,295 |

3 |

|

2001 |

95,967 |

44,784 |

47 |

4,285 |

4 |

2,296 |

2 |

3,903 |

4 |

3,033 |

3 |

|

2002 |

79,725 |

33,798 |

42 |

4,041 |

5 |

2,496 |

3 |

4,266 |

5 |

2,745 |

3 |

|

2003 |

69,289 |

30,238 |

44 |

3,313 |

5 |

2,241 |

3 |

3,359 |

5 |

2,790 |

4 |

|

2004 |

83,128 |

40,394 |

49 |

3,632 |

4 |

2,633 |

3 |

3,635 |

4 |

3,170 |

4 |

|

2005 |

70,266 |

31,337 |

45 |

3,857 |

5 |

2,159 |

3 |

3,319 |

5 |

3,166 |

5 |

|

2006 |

74,326 |

38,999 |

52 |

3,563 |

5 |

2,237 |

3 |

2,891 |

4 |

3,014 |

4 |

|

2007 |

86,219 |

51,326 |

60 |

3,711 |

4 |

2,510 |

3 |

4,112 |

5 |

2,735 |

3 |

|

2008 |

71,019 |

44,277 |

62 |

2,870 |

4 |

2,009 |

3 |

3,465 |

5 |

2,003 |

3 |

|

2009 |

60,009 |

34,490 |

57 |

2,982 |

5 |

1,662 |

3 |

3,987 |

7 |

2,135 |

4 |

|

2010 |

66,176 |

38,833 |

59 |

3,216 |

5 |

2,124 |

3 |

3,527 |

5 |

2,194 |

3 |

|

2011 |

74,205 |

46,969 |

63 |

3,444 |

5 |

2,330 |

3 |

2,230 |

3 |

2,176 |

3 |

|

2012 |

80,015 |

53,877 |

67 |

3,355 |

4 |

2,927 |

4 |

1,925 |

2 |

1,824 |

2 |

|

2013 |

96,753 |

71,953 |

74 |

3,362 |

3 |

3,052 |

3 |

1,830 |

2 |

1,666 |

2 |

|

2014 |

109,147 |

85,900 |

79 |

3,678 |

3 |

2,687 |

2 |

1,446 |

1 |

1,499 |

1 |

|

2015 |

124,484 |

102,119 |

82 |

4,154 |

3 |

2,493 |

2 |

1,108 |

1 |

1,329 |

1 |

|

2016 |

131,051 |

110,003 |

84 |

4,601 |

4 |

2,161 |

2 |

1,065 |

1 |

1,178 |

1 |

|

2017 |

136,393 |

117,522 |

86 |

4,770 |

3 |

2,066 |

2 |

955 |

1 |

828 |

1 |

Source: U.S. Department of State Bureau of Consular Affairs, “Nonimmigrant Visa Issuances by Visa Class and by Nationality: FY1997-2017 NIV Detail Table,” accessed March 20, 2018.

Employment Authorization for the H-4 Visa Category

On May 26, 2015, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) implemented a new regulation which permitted certain H-4 dependents to work in the United States. Under the regulation, the only H-4 dependents eligible to apply for employment authorization are H-4 spouses of H-1B nonimmigrants who are in the multistep process of becoming lawful permanent residents (LPRs) or who have H-1B status under the amended American Competitiveness in the 21st Century Act of 2000.

Work authorization for eligible H-4 spouses is unrestricted, meaning that the H-4 dependents can work for any employer. Yet their work authorization, like their immigration status, is dependent on the H-1B worker maintaining a valid immigration status.

In the two years that followed implementation of the regulation authorizing employment for certain H-4 spouses, the U.S. government approved nearly 105,000 H-4 applications for employment authorization (Table 2).

Table 2: Approved Employment Authorization Documents (EAD) for H-4 Spouses of H-1B Visa Recipients, FY 2015-2017

|

Fiscal Year |

Number of Approvals of EADs for H-4 Spouses |

|---|---|

|

2015 |

26,858 |

|

2016 |

41,526 |

|

2017* |

36,366 |

* Numbers reported by USCIS Oct. 1, 2016, through June 29, 2017.

Source: U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, “EADs by Classification and Basis for Eligibility, Oct. 1, 2012 – June 29, 2017,” Immigration and Citizenship Data, updated Feb. 28, 2018.

Advantages of Allowing H-4 Spouses to Work

Authorizing H-4 spouses to work is advantageous for several reasons. Notably, allowing spouses to work brings the United States in line with other countries competing to attract talented foreign nationals.

The highly-skilled individuals U.S. employers hope to attract and employ on a H-1B nonimmigrant visa often have a spouse or family to consider. The potential worker may have a spouse with an established career or a family needing the support of two working parents. If a spouse retains the option of being employed, the U.S. employer can provide a more appealing and competitive job offer.

Highly-educated immigrants are more likely to choose a country where immediate family members are welcome. For instance, when immigrant scientists and engineers are asked why they chose the United States as a destination, the most common response is “family-related reasons.”

In addition, the ability to work can facilitate the integration of H-4 spouses into the United States and reduce isolation. Since the majority of H-4 spouses are female, authorizing their employment also empowers women to contribute their skills to American society, while strengthening their families’ economic well-being.

An Uncertain Future for H-4 Employment

In 2017, President Donald Trump issued an executive order that outlined changes to the employment eligibility for H-4 spouses. The “Buy American and Hire American” executive order announced the administration’s intent to revoke the regulation permitting certain H-4 spouses to apply for work authorization. The regulatory agenda published in Fall 2017 reaffirmed this intention, though few details have been made available.

In order to change the employment eligibility of certain H-4 spouses, USCIS first will have to propose a new regulation which will invite comments from the general public. The agency must consider and respond to those comments before publishing a final rule that then takes regulatory effect.

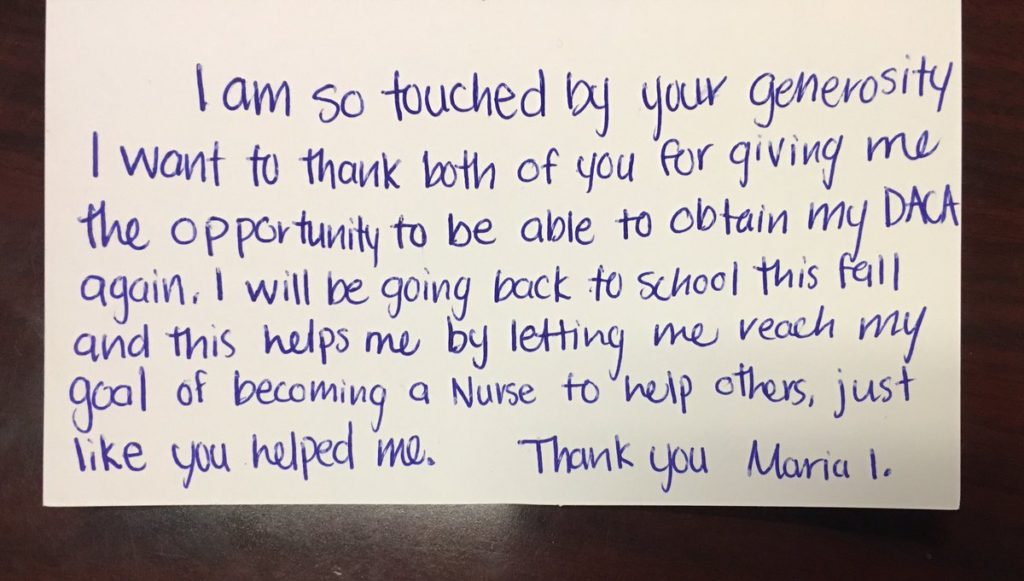

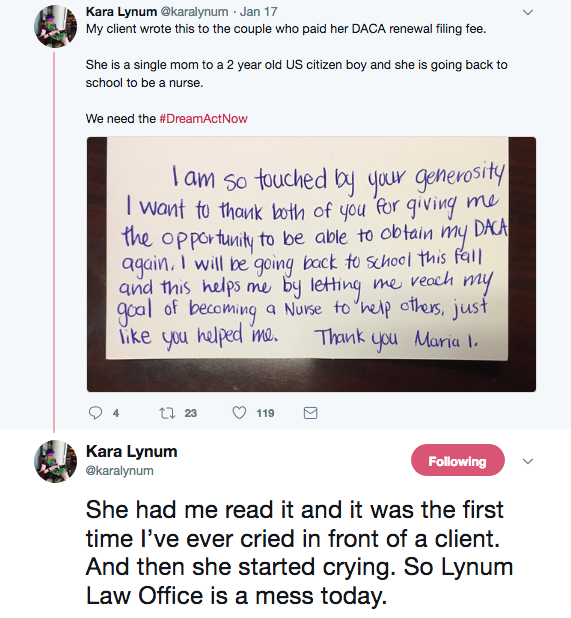

Stepping Up to Help DACA Recipients

When Kara Lynum speaks, people listen! Not only do they listen: they donated more than $30,000 to pay DACA renewal fees in just one month.

Kara started with an MPR interview, talking about Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) after a federal judge’s order allowed renewal applications. “Some people are scrambling now who don’t have $495 sitting in the bank,” she told Tom Weber on January 16.

Listeners responded, with one person offering to pay the filing fee for “at least one person, maybe two.” That donor paid the filing fee for one of Kara’s clients, a single mom with a two-year-old U.S. citizen child. That client wrote the thank you note pictured above.

DACA protection from deportation and permission to work lasts for only two years at a time. Then each recipient has to file for a renewal. While two federal judges have ordered the Trump administration to accept renewal applications, no one knows how long those court orders will stay in effect, and Congress still hasn’t done anything to help DACA recipients. All of that makes renewal applications crucial.

Kara tweeted out the thank you note (above) and her response:

Kara’s tweets started a wave of support. She contacted the Immigrant Law Center of Minnesota to set up a way to accept the donations and distribute them to people who needed help paying the DACA renewal fee. A friend of Kara’s set up a Venmo account to accept smaller donations and add them up. No stranger to activism, Kara was named as a 2016 Attorney of the Year by Minnesota Lawyer magazine, in part for her four volunteer trips to represent detained migrants, “driving some 1,300 miles south each time to put in 12-hour days working pro bono with migrant women and children languishing in detention centers in Texas and New Mexico.” She was also named one of four recipients of the Immigrant Law Center of Minnesota’s 2015 National Advocate of the Year award. In 2017, City Page lauded her work at the airport, among the volunteer attorneys who showed up to help people through the chaos that followed the first Trump travel ban.

Thanks to Kara Lynum and to all those who have stepped up to help DACA recipients during this difficult time. Want to donate?

ILCM has set up a way to donate to pay filing fees for Dreamers renewing their DACA status. Because of the complexities of tracking, ILCM can accept DACA fee donations only in the amounts of $495 (full fee) or $247.50 (half a fee). To donate, start here. Check the line for “other one-time contribution,” and fill in $495.00 or $247.50. Then click on “continue” at the bottom of the page. On the next page, write in “DACA filing fee” in the acknowledgement box. Donations for DACA fees are NOT tax-deductible. Thank you for supporting Dreamers!

Cooking Up Support With Eat For Equity

Eat for Equity invited people to their Welcome Table to “try amazing new foods in the context of the refugee/immigration stories. You will meet new friends and learn more about the vibrant communities that are in our state…all the while supporting an amazing cause!!” Their volunteer chefs cooked up a feast for 200 friends and supporters on March 3 at the Paikka Event Center, raising nearly $3,000 to support ILCM’s work.

Eat for Equity organizes volunteers to prepare and serve food at events benefiting nonprofits throughout the year. For this event, Paikka donated its space, and Lake Monster Brewery and Fair State Co-op donated beer. Each chef introduced their contribution to the evening’s meal, and ILCM’s John Keller spoke briefly about immigration issues and the work of ILCM. Guests also enjoyed free paintings and hands on printmaking by the Living Proof Collective, Taylor Baldry, and Cori Lin.

While part of the goal is fundraising, another part is accessibility. Eat For Equity’s events come with some pay-what-you-can tickets as well as opportunities to volunteer as a way of paying your way.

SAVE THE DATE: Eat for Equity’s Welcome Table offered a great opportunity to celebrate and support ILCM at the same time. The next opportunity comes on June 1, with a fundraising gala at the Minneapolis Marriott City Center in downtown Minneapolis. Save the date! Details will follow in April.

The amazing food at the Welcome Table on March 3 included:

- a Ugandan street food called Rolexes to start the meal,

- greens with oyster sauce and taro cake,

- a Bulgarian feast, with Stefaniloaf, a cucumber herb salad, and a potato, mushroom, and leek tart,

- and for dessert: flan de queso!

Welcome New ILCM Staff! Spring 2018

Four new full-time staff members and 12 interns started work at ILCM in January and February, marking expanded capacity to meet the growing need for immigration assistance in Minnesota.

Yer Vang grew up in Minneapolis, after her family arrived from a refugee camp in Thailand. She graduated in 2015 from Minneapolis Business College with a legal office administration degree. “I learned how to do both office and legal work at the same time,” she explains. She worked for a law firm in Minneapolis before she started working at ILCM as a legal assistant in January. Her experience also comes from closer to home, as she helped family members through the process of filing immigration petitions. Now she works on naturalization cases as well as adjustment of status and family petitions.

Yer said she wanted to work at ILCM “so I could help more people.” Now a U.S. citizen, Yer said:

“I am able to use the natural skills I have to help people and make sure they are safe and not have them worry about the risk when they are here. Supposedly this is a safe country – that is the reason why they came here. I want to assure them that we do want them here.”

Sylvie chose to move to Minnesota because, she said, it is “a good place to live permanently.” At ILCM, she will work as a policy advocate.

Mirella Ceja-Orozco started at ILCM when she was in her first year of law school at Hamline, continued as a pro bono lawyer in private practice, and has now returned as a staff attorney. Her commitment to immigration law is personal: “My father was deported when I was very young,” she explains, “and I have a very mixed-status family. As one of the people with legal status, it was my obligation as a child to be the interpreter, sometimes to be the person to drop off an overnight bag for a person who was being deported.”

Mirella moved to Minnesota for law school, arriving for her August orientation “with a puff coat and snow boots on—that’s how California-sheltered I was!” Now, she says, she is “a super big Minnesota advocate,” and happy to be here and with ILCM.

Joyce Bennet Alvarado moved to Worthington in February to become the second staff attorney in the ILCM office there. After growing up in Honduras, she came to Minnesota to attend the University of St. Thomas Law School, graduating in 2017. Joyce says she liked St. Thomas’s emphasis on being a lawyer as a vocation, not just a profession.

Working in Worthington is her first experience of living and working in a rural area. “I really like it because the community is so involved,” Joyce says. “There are so many groups here that are helping immigrants. We work with churches, with the crisis center, with different agencies, so that’s pretty exciting.”

Along with these new staff members, ILCM welcomes 12 new interns in spring semester. Among them:

Mon Non was two months old when he arrived in the United States with his family as refugees from Burma. Mon is now in his first year of college at the University of Minnesota, after graduating from St. Paul Central High School. He’s also a professional photographer, and the photos in this article are part of his internship contribution to ILCM.

Andrea Duarte-Alonso is one of two interns from St. Catherine University who are assisting with Detainee Legal Assistance calls. She comes from a Mexican immigrant family in Worthington, where she first encountered ILCM and John Keller. Now a junior at St. Kate’s, she has an ambitious focus on political science, communications, journalism, and women’s studies, and is interested in pursuing a career in immigration law.

Anne Applebaum, ILCM Win Statewide Recognition for Pro Bono Work

Two awards marked the success of the Pro Bono program of the Immigrant Law Center of Minnesota (ILCM). The first came to Pro Bono Director Anne Applebaum, as the Minnesota State Bar Association honored her with the 2018 Bernard P. Becker Legal Services Emerging Leader award. This award is presented each year to honor dedicated service, outstanding achievements and a demonstrated commitment to provision of zealous and skilled legal representation by an attorney employed by a private, nonprofit agency that provides legal services to low-income and disadvantaged Minnesotans. The second award came from the Minnesota Corporate Pro Bono Council, which honored ILCM as its “Partner of the Year for 2017.

Anne joined ILCM as an AmeriCorps VISTA volunteer in 2010, leaving private practice to dedicate herself to a career in public interest law with a specific interest in immigration law. In 2011, Anne became ILCM’s pro bono coordinator, and was promoted to Pro Bono Director the next year. She has led ILCM’s pro bono programming since that time.

Anne’s leadership and innovation have built one of Minnesota’s best pro bono programs. Anne has steadily increased the number of active volunteer attorneys throughout her tenure. In 2017, 229 pro bono attorneys represented low-income clients in nearly 500 immigration cases. Together, they reported more than 3500 donated hours, an all-time high for the organization.

“Her work reflects the highest level of client service and ensures that our pro bono trainings and representation are excellent,” says ILCM Executive Director John Keller. “The impact of her sustained hard work and dedication has been extensive, benefitting both the legal community and Minnesota’s immigrant and refugee communities.”

The Minnesota Corporate Pro Bono Council brings together pro bono leaders from businesses’ internal legal departments to increase the level of pro bono work being done by in-house counsel, paralegals and other staff. Besides direct service to clients, they offer CLE, training and pro bono opportunities that are open to anyone in the law departments of Council member companies. Through each case and each substantive immigration matter business attorneys take on, they become aware of and engaged with immigrants from all over the world on the essential immigration issues of our times.

This year, says Council President David March, “We wanted to recognize ILCM, and in particular, Anne, for creating innovative opportunities for in-house counsel, paralegals and staff to work on a variety of immigration matters through the DACA clinic, DACA renewal trainings, etc.”

Thanks to the MSBA and the Minnesota Corporate Pro Bono Council for this recognition—and thanks most of all to the pro bono attorneys, paralegals, and support staff who partner in ILCM’s work.

Fighting trafficking and abuse: Camila’s story

Trafficked, abused, living in fear—and then Camila’s* life got worse. By the time she met the Immigrant Law Center of Minnesota through Susan Jorgensen Flores, Camila was sitting in jail, separated from her children, and in danger of deportation.

Camila was born in Tamaulipas, Mexico, and raised by her grandmother until she was 16 years old. Then her grandmother sold her to a 29-year-old man for $2,000. He was physically and emotionally abusive from the start. They never legally married. When Camila became pregnant, he left for the United States. He left her behind with his aunt, who also abused her.

Before the baby was born, Camila escaped from the aunt and came to the United States. She rejoined her abusive partner in North Carolina. and their son was born in September 2006. A daughter was born in 2008.

The abuse continued. When she became pregnant with a third child, her partner demanded that she have an abortion, and she refused. He said he would leave, and she was happy to see him go.

By the time her second daughter was born, Camila was 21 and living in Tampa, Florida. The father of the children eventually visited them there. He was not very interested in the daughters, but took their son away and would not return him. Camila has not seen her son since then, and as far as she knows he is with his father in Mexico.

After some time, she became romantically involved with José, a construction worker. He traveled to different states for months at a time, leaving her and her daughters in Florida. When she became pregnant with his son, he became abusive and extremely jealous, and then insisted that she and the children travel with him. He was a heavy drinker, who also got involved in drugs, and remained physically and emotionally abusive throughout their relationship.

Camila and José and the children lived in Minnesota for some time, and José paid the rent, but nothing else. He also forbade Camila from working. She kept the family going with food from a food shelf and the help of a friend, Rosita*, who would often feed the children and Camila.

Desperate for a way to pay monthly expenses, Camila eventually applied for assistance for her U.S. citizen children. She did not list José as a household member and did not list his income, as he went for weeks without coming home and did not provide any money to her.

In 2014, she was charged with wrongful receipt of assistance, because José did pay the rent and sometimes stayed in the home. José hired a private attorney who got Camila into diversion, but with a guilty plea sitting in the prosecutors file that would be submitted to court if she violated any of the terms of her diversion. One of the terms of this agreement was that she must not leave the state of Minnesota.

A few months later, Camila was taken to the hospital as a result of physical abuse by José. He was charged and ultimately convicted of domestic assault.

That made Camila eligible for a U visa, a special visa reserved for undocumented immigrants who are crime victims, but who step up and cooperate with police and the criminal justice system. The county has to certify that a crime victim qualifies for a U visa. Unfortunately, even after this certification, the victim faces a very long wait. There’s a cap of 10,000 U visas per year, and there are more than 200,000 applications pending.

José was enraged by her having called the police and when he got out of jail, he took Camila and the children to Kansas, where he continued to be abusive, both emotionally and physically.

In 2016, Jose learned that there was a warrant for Camila’s arrest in Minnesota, because she violated the terms of the diversion agreement when she left the state. The abuse worsened at that point with him constantly threatening to turn her into the police, get her deported, and take her children away.

She eventually tired of the threats and abuse and in August 2017 she signed a Delegation of Parental Authority (DOPA) form, giving custody of her three minor children to her friend Rosita, who still lived in Minnesota.

Then Camila turned herself in to the police in Kansas. She was transported to Minnesota and ICE picked her up shortly thereafter. Under the terms of the diversion agreement, a guilty plea was immediately entered, and ICE picked her up.

The guilty plea was considered an aggravated felony by the immigration judge, who denied her bond and kept her in jail. Her two daughters were brought to Minnesota to live with Rosita, though José refused to release his son, who continues to live with him in Kansas to this day.

ILCM’s Susan Jorgensen Flores got involved when sentencing was still pending with the Public Defender’s office. Susan heads up ILCM’s assistance to public defenders across the state. After much work and excellent cooperation between the public defender, the county, and the judge, the guilty plea was withdrawn, on the basis of an underlying substantive defect in the charge. Then the criminal case was dismissed—be gone aggravated felony!

On December 20, 2017, five days before Christmas, at a new hearing, the immigration judge set bond at $1500. No one had the funds to pay the bond. Camila’s friend Rosita has four children of her own and had been supporting Camila’s daughters for nearly four months by that point. She did not have anything extra to spare.

Camila had no family in the United States other than her minor children, and had no friends other than Rosita, due to the isolation imposed on her by her abusers over the years. She did have an advocate from CADA of Watonwan County and she did have a signed U certificate from Watonwan County. No one had money for a bond.

ILCM went looking for money to pay the bond. On December 22, the Freedom Fund organization paid the bond and Camila was reunited with her daughters for Christmas!

*We have changed some names in this story. As a matter of policy, we usually change the names of immigrants when telling their stories. While the stories are real, and while the individuals have agreed to let us use their stories, we choose to protect their privacy by not using their real names.