Archives

U.S. is denying passports to Americans along the border, throwing their citizenship into question

https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/the_americas/us-is-denying-passports-to-americans-along-the-border-throwing-their-citizenship-into-question/2018/08/29/1d630e84-a0da-11e8-a3dd-2a1991f075d5_story.html?noredirect=on&utm_term=.7a9ab4ee718e

Rocky beginning, growing acceptance: The Somali experience in Faribault

Hennepin County finalizes deal for legal services for residents facing deportation

Becoming a Citizen: Quick Facts

Every year, hundreds of people come to the Immigrant Law Center of Minnesota for help in becoming a citizen. The process can be long and complicated. Here are a few quick facts about citizenship.

- Anyone born in the United States is a citizen.

- Someone who is born to a U.S. citizen parent is a citizen (usually).

- For someone who is not a U.S. citizen by birth, the process of becoming a citizen is called naturalization.

- Applying for citizenship requires a 20 page form with 18 pages of instructions, and numerous documents such as birth certificates, marriage certificates, divorce decrees, tax returns, pay stubs, etc.

- The application fee is $725.

Who can apply?

While there are some exceptions for spouses of U.S. citizens, immigrants serving in the U.S. military, and children, the general requirements are that the immigrant applying for citizenship must:

- Be at least 18 years of age;

- Be a lawful permanent resident (green card holder);

- Have resided in the United States as a lawful permanent resident for at least five years (three years for spouses of U.S. citizens);

- Have been physically present in the United States for at least 30 months;

- Be a person of good moral character;

- Be able to speak, read, write and understand the English language;

- Have knowledge of U.S. government and history; and

- Be willing and able to take the Oath of Allegiance

The catch comes in legal residence requirement, also known as having a green card. In order to become a citizen, you first have to get that legal permanent resident visa. You may have heard people asking, “Why don’t they just get in line?” For most people, there is no line, no way at all to get in. (For more information, see Getting to Know New Minnesotans, Part Three: Who Can Get in Line?)

How long do you wait?

For permanent residents who qualify and apply, the line from application to citizenship can be very long. In 2017, the backlog of citizenship applications to the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) grew to 735,000. The official USCIS calculator says someone in Minnesota who files a completed N-400 form and all necessary documents will wait 15-19.5 months for a decision. The wait time varies from state to state, and in some places is as long as two years.

Despite the obstacles, immigrants persevere. According to the most recent USCIS information:

- In 2016, 8,573 Minnesota immigrants became U.S citizens.

- In the entire country, 753,060 immigrants became U.S. citizens.

- Almost half of all Minnesota immigrants are U.S. citizens.

Facts About Family Separation for Asylum Seekers

This fact sheet is published by the Catholic Legal Immigration Network, and dated August 9, 2018.

For information on what you can do to help, see Family separation at the border: How you can help

fact-sheet-on-family-seperation147 Arrested After Immigation Raids in Minnesota, Nebraska

ICE arrested 14 “owners and managers” in the alleged conspiracy, and 133 of their alleged victims.

Facts About Immigration Courts

El Consulado Móvil Guatemalteco Visitará Minneapolis

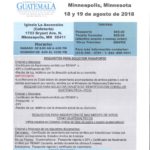

El consulado móvil guatemalteco visitará Minneapolis los días 18 y 19 de agosto. Detalles en pdf adjunto. (Ingles abajo)

Consulado Movil en Minneapolis Minnesota 18 y 19 agostoThe Guatemalan consulate will visit Minneapolis on August 18 and 19, 2018. They will be at the Church of the  Ascension, 1723 Bryant Avenue North, Minneapolis from 8 a.m.-4 p.m. on Saturday, August 18 and from 8 a.m.- noon on Sunday, August 19.

Ascension, 1723 Bryant Avenue North, Minneapolis from 8 a.m.-4 p.m. on Saturday, August 18 and from 8 a.m.- noon on Sunday, August 19.

The mobile consulate will accept applications for passports, for consular ID cards, and to register Guatemalan citizenship for children born in the United States with a Guatemalan father or mother. Some other forms will also be processed. For more information, call (312) 540-0781 or 1-844-805-1011

United States Must Extend Temporary Protected Status for Somalis

July 13, 2018 – As Somalia struggles with civil strife and bombings, the United States must extend the Temporary Protected Status (TPS) for Somalis living here with that status. Their TPS is set to expire on September 18, 2018. The Department of Homeland Security will issue a decision on whether or not it will extend TPS by July 19.

Temporary Protected Status for Somalis was first established in 1991, and has been extended since then. The U.S State Department tells Americans not to travel to war-torn Somalia, warning that if you do go to Somalia, you should first make a will, leave a DNA sample (presumably so your remains can be identified), and “discuss a plan with loved ones regarding care/custody of children, pets, property, belongings, non-liquid assets (collections, artwork, etc.), funeral wishes, etc.”

When Somali TPS was last extended in 2016, the Federal Register notice said, “Somalia continues to experience a complex protracted emergency that is one of the worst humanitarian crises in the world.” The situation inside Somalia has not significantly improved since then.

“The Department of Homeland Security must extend TPS for all Somalis who currently have that status, and should also redesignate TPS to allow others to apply,” says ILCM Executive Director John Keller. “Previous DHS decisions ended TPS for about 300,000 people from countries including El Salvador, Haiti, Honduras, Nicaragua, Nepal, and Sudan. People with TPS have lived here for decades, working, contributing to their communities, and raising families. Ending TPS means separating mothers and fathers from 273,000 U.S.-born children. Congress must act to create a path to permanent legal residence for all people with TPS.”

“The current political and humanitarian conditions in Somalis qualify for TPS to be reinstated in Somalia”, says Council on American Islamic Relations-Minnesota Executive Director Jaylani Hussein. “Minnesota is home to the largest Somali American community and home to TPS holders. Today, these families and their communities are urging for Congress to pass legislation that provides permanent status for these hardworking families.”