News > Immigration In Minnesota

To All Those Who Supported Me: A Thank You Letter

Posted on Dec 23 2019

“The media is currently focusing on the achievements of immigrants. What have they done here? How are they extraordinary? I think it’s more important to share how I got where I am, what others have done for me. What I’m currently doing right now isn’t as extraordinary.”

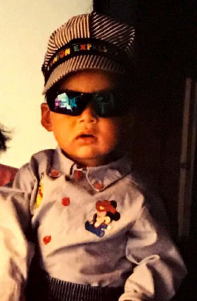

José was born in Ecatepec, Mexico – a city of 1.6 million in the Estado de México. His parents had every intention of raising their children in Mexico and lived in Ecatepec until he was three years old. When they didn’t have enough money to buy diapers and milk, however, they decided to return to the United States.

José’s parents had first met in Minneapolis, where they both worked at a meat factory. At first, José’s dad was too shy to say anything to his mom, so he told an uncle that he liked that young woman. The uncle told that young woman, and soon after José’s parents began dating. They returned to Mexico to get married and start a family. José’s parents wanted to raise their sons in Ecatepec, but eventually knew that returning to the United States would be best for their family. They entered illegally—their only option. No visas were, or are, available for families like his.

They did not succeed on their first attempt to cross the border, nor on their second. José remembers being caught at least twice and being sent to a detention center. He remembers being separated from his parents in the detention centers and having to ask to see his mom and/or dad because women and men were separated by gender.

“I remember walking by looking at the border control officers. I remember looking at them and thinking why wouldn’t they let us go.”

José was three and a half, his brother was one, and his mother was pregnant with his youngest brother when they made their final journey from Mexico to the United States, together with three other family members – his uncle, and two of his aunts. His mom was five months pregnant and his aunt seven months when they crossed. This made things more difficult. José’s parents used a coyote, a paid guide who was also a family friend, to help them cross.

The only thing José remembers clearly from the journey is when he got separated from his parents. On the border there was a chain link fence with a hole just big enough for small children to fit through. At seven months pregnant, his aunt was unable to fit through the hole, so she had to jump over it, which was dangerous since she was due in a couple months. The coyote and José’s extended family members climbed over the fence before José crawled through. His father, carrying his brother, and his mother were to come next—but then Border Patrol arrived. They stayed behind, hiding in the bushes, as the Border Patrol loaded José and the coyote into their truck.

“I remember crying and having to get in a pick-up truck. I remember hearing, ‘Don’t cry Toñito, don’t cry,’ but of course I continued crying.”

The attempt during which José and the coyote were apprehended, ended up being successful for his parents and brother. They were able to cross after José and the coyote were taken away in the truck. His parents waited in the agreed-upon hotel for a couple days. They were afraid that the coyote would not be able to get José to them. They had planned to wait one more day before his father would return to Mexico to look for José when the coyote arrived with him, reuniting the family. Once they were reunited, they took a bus from Douglas to Phoenix.

…

“I definitely look up to my parents. Whenever I try to put myself in their shoes, I’m left in awe. They were in their 20s and they had to decide everything: if they wanted to move, where they wanted to go… giving up every sense of opportunity and familiarity. Neither of my parents attended high school. Neither of them spoke English.”

They lived with José’s aunt, a naturalized U.S. citizen, in the basement of her house in a suburb of the Twin Cities metropolitan area. Living on the top floor were his aunt and uncle and cousins, who are around his age.

“It was always fun, because after school we could play around in the neighborhood. I remember specifically that we lived in a cul-de-sac. During the winter when it snowed, the snowplow would come through and afterwards there would be a huge pile of snow. We had a lot of snow ball fights.”

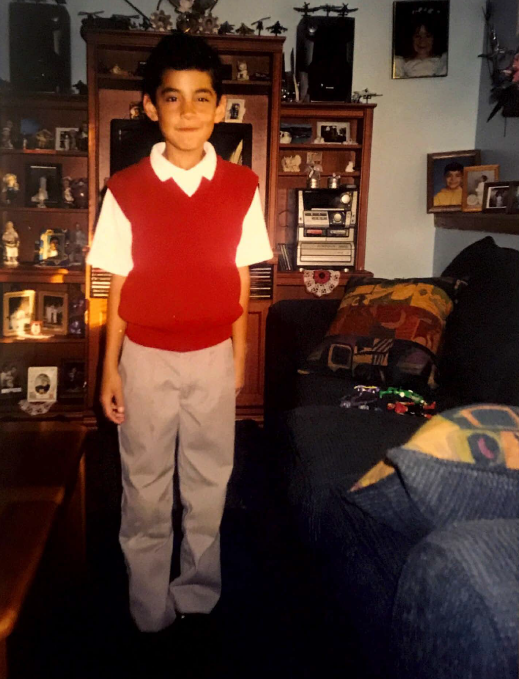

José’s parents worked hard, determined to make a good life for their sons. They sent them to a Catholic school in Minneapolis. English was difficult for José and he was in ESL until 4th grade, in part because he had trouble focusing in school and would skip ESL classes. His brothers had an easier time. They had grown up speaking English and did not need ESL. In 8th grade José switched to a different Catholic school to be closer to home. This new school was predominantly white.

“My old school was actually pretty diverse. The classes were really small, and my cousins and brothers attended the same school. I felt like I could be myself. I was in an environment where at least some people looked like me. At my new school, I felt out of place and uncomfortable, honestly … It’s hard, because at that age you’re in that struggle for identity, looking for people you can connect with, identify with. Suddenly I was put into environment of affluent people. People who looked and acted differently. This was foreign to me.”

During those years, his dad bought, fixed, and sold cars—all out of their garage. José remembers handing his dad tools and visiting the junkyard for spare parts. Even during freezing Minnesotan winters, they worked on cars out in the garage. José’s brothers also helped in the garage, although it was not very efficient with all three boys working at once, given their tendency to stop working to “play around and throw things at one another.” José’s mom also helped in the garage at times.

“Sometimes our entire family would be out in the garage working on a car. Family has always been an important aspect of growing up.”

José was good at sports and thinks this helped him socially. Soccer served not only as an outlet, but also as a way to connect with fellow players. He was never bullied, but sometimes joined with fellow athletes in picking on others.

“When you’re put in an environment where you’re an outsider you try to assimilate by doing certain things you wouldn’t normally do. You do your best to assimilate, to fit in. It’s hard when your peers don’t understand you. You know that you’re different, but you don’t want to/can’t explain it to them. How could I explain that ‘home’ for me is just ‘limbo’? That for me, home is the disparity of not knowing where I truly belong. It’s a conflict of where I belong.”

Looking back on his adolescence, José thinks he was depressed. “I didn’t know what that was when I was younger. I felt different somehow. Something about me was different.” He felt resentment toward his parents. He was ungrateful because he felt out of place somehow and blamed his parents for bringing him to a place where he didn’t belong. He remembers asking them, “Why did you bring me here?”

“There was a sense of feeling ashamed. My friends were getting permits. I remember thinking, ‘Wow I can’t do this… why not? I’ve done everything the same and yet I’m restricted somehow…”

José truly understood the weight of his parents’ actions during his senior year of high school while applying for college. He had always taken advanced math and English classes, but not AP classes. His grades were good—not great—but good.

“When I graduated high school, I didn’t have that many options. My grades were average. There’s nothing for someone who wasn’t born here with average grades. I didn’t know I would be considered an international student… and have to pay international student fees. I wasn’t eligible for FAFSA either. I realized, ‘I gotta work for this. Like physically work for this.’ That wasn’t easy. Friends were going to college and I couldn’t. Reality hit me. I always knew I was different, but I didn’t know how. How severe those implications were. I started to reflect on how I got to where I was, and for the first time I asked myself, ‘What has been done to get me here?’”

After all his parents had done for him, failure was not an option.

…

In 2012, President Barack Obama established Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA). DACA was a temporary and partial solution for Dreamers, immigrant children who had no legal status but had been brought to the United States as children and grew up here. José was part of the first wave of DACA applicants. After the Immigrant Law Center of Minnesota (ILCM) put on a workshop at Green Central Elementary School, he applied with help from ILCM and family members.

José remembers the application being relatively straightforward. “The application is based on what you do. Are you a threat to American society?” He had to go through his parents’ old accordion files to find proof that he went to school, his grades, old diplomas and certificates. José even contacted his old soccer coach to request a letter saying he had played soccer on the team. “A lot of this seemed irrelevant,” he recalls, “but it was part of the evidence file that we had to give to prove that I had ‘upstanding moral character’ and had been in the country continuously since June 2007, as required by the program.”

After receiving DACA, José enrolled in a technical school program for auto mechanics. He got a job at a small shop during his first year in the program, and then a better job at a car dealership. He switched from technical school to community college, and then to the University of Minnesota, majoring in economics. Along the way, he started working in accounting jobs, and worked in automotive and accounting jobs throughout his college years. José graduated from the University of Minnesota with a degree in economics in December 2018, and now plans to pursue graduate study in economics or statistics.

José says what he has accomplished or will accomplish is not really the point: he owes a lot to his parents, who brought him to the United States, and to others who have supported him since then. They are his heroes. They are the ones whose stories are most important to him.

“They are the unsung heroes of what I can accomplish. They live vicariously through me. They’ll never get recognition. What my siblings and I accomplish is their fulfillment.”

If there is one thing that José hopes people take away from hearing the stories of immigrants like himself, it is this:

“There are a lot of positive people here. We don’t go around telling our stories because it’s dangerous for us. The news can be distorting when they focus on the negatives.

“It’s important to be more open. More humane. And more caring. Because I think in the end, this country identifies with life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, and we are all searching for this.”

Growing up, José was acutely aware of immigration and the situation at the southern border. As he grew older, he increasingly understood the sacrifices his parents had made to make a life for their family in the United States. He says his parents are selfless, focused completely on the future of their children. They have worked jobs they didn’t like, given up any chance for their own education, and moved far away from other family members. They have not seen siblings, nieces, or nephews in decades.

“My parents sacrificed so much for my brothers and me. I’ve been talking about the challenges I have faced here, but their situation is worse than mine. When my mom’s dad died, she was adamant about attending his funeral. At the time, I was old enough to understand what had happened, but not old enough to know the sadness. What I definitely understood, however, was that if my mom went to the funeral, she could probably never come back.”

“Mom cried hysterically. She was fixed on going. She hadn’t seen him for a long time. But she didn’t go.”

“Dad did the same thing when his father died. He decided not to go. And last year Dad’s brother died. Dad hadn’t seen him in over 20 years, but he couldn’t go to the funeral.”

“My parents haven’t experienced cultural comforts, security in over twenty years.”

José’s parents filed a family visa petition application in the 1990s. They are still waiting.